The Holocaust Gets Graphic

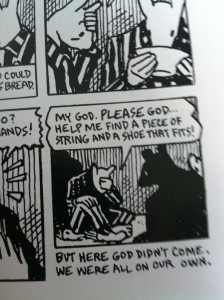

We are taking a different road this time, reviewing our first graphic novel, MAUS I and II by Art Spiegelman. In truth, this is not the first graphic novel Lara has read, but it is Jennifer’s initial foray into the genre—and we may have a convert to this exciting and (Lara thinks) oft misunderstood form. Part memoir, part comic book, part postmodern dip into storytelling, MAUS I and II (there are two volumes, which should really be read together) bring to life—animal life—a tale of surviving the Holocaust. Jews are depicted as mice, while Germans are depicted as cats. Poles are depicted as pigs. It is interesting to note that the faces of the animals are represented as masks, with the strings with which the masks are tied onto human faces often showing.

We are taking a different road this time, reviewing our first graphic novel, MAUS I and II by Art Spiegelman. In truth, this is not the first graphic novel Lara has read, but it is Jennifer’s initial foray into the genre—and we may have a convert to this exciting and (Lara thinks) oft misunderstood form. Part memoir, part comic book, part postmodern dip into storytelling, MAUS I and II (there are two volumes, which should really be read together) bring to life—animal life—a tale of surviving the Holocaust. Jews are depicted as mice, while Germans are depicted as cats. Poles are depicted as pigs. It is interesting to note that the faces of the animals are represented as masks, with the strings with which the masks are tied onto human faces often showing.

Lara: Okay, I am totally excited that you read a graphic novel! I have been a super fan of the genre since I read Persepolis in 2010 and learned that not all graphic novels are about superheroes.

So I have to know what you were thinking when we made the decision to read this. Were you intrigued, unsure, expecting to hate it? My inquiring mind wants to know!

Jennifer: Believe it or not, I went into it fairly open—more open than I went into a couple of other books we’ve tried out such as The Hunger Games trilogy and The Husband’s Secret. Since I’m so late to the game, I had heard enough to know there was something to it beyond the traditional comic book.

By the way, I have to let you and our adoring fans know that I have a strong and vocal contingent in my inner circle of friends who is freakin’ nuts about comic books. These geeks—who are otherwise cool—even dress up like superheroes and go to Comic-Con. So, I need to be careful here. I have to admit that I’m not into comic books, but I’m very interested in the things weird people do. I’m kinda hoping we go to Comic-Con soon, so I can soak in the weirdness. I just like freaks. Tim has a stash of comic books that I’m hoping he sells. I want the money to buy the kids new beds.

I have no question whatsoever, really, that the graphic novel is a valid or legitimate art form. Of course it is, right? It’s amazing! The author/artist is just that: an author and an artist. MAUS I and MAUS II are great; I’ll make my kids read them. They’re also the kind of thing one wants to own—maybe unlike a novel, even a really great novel, because words can be borrowed at the library. The visual arts may beg for personal possession. (This is sounding weird.)

I guess the question, then, is whether these graphic novels, MAUS among them, are actually literature. Or are they something else? This is a highly academic debate, a little like trying to figure out how many angels can dance on the head of pin.

Lara: I am so thrilled you enjoyed the books! I think books like MAUS I and II, as well as Stitches by David Small (which was a National Book Award finalist) are literary, while also being artistic. So, yes, they count. They are Art. However, books like The Watchmen are not literary, but they are Art too. At least, in my humble opinion, that’s what they are.

Let me ask you this: Do you think taking a topic like the Holocaust, and sharing it in a comic book form, lessens its seriousness?

Jennifer: On your first point, I’m really not so sure—but we don’t have to go here because it might be absurd. What is literary? Something that involves words? I’ve made a brief argument elsewhere that there might be something called literary TV (here is an article that develops this notion better than I do: “’Girls,’ ‘Mad Men,’ and the Future of TV-as Literature” from The Atlantic – also check out the link within this link on “Clues That Lead to More Clues That Add Up to Nothing”). I began thinking about this when I became obsessed with “Lost,” which turned out so badly; and it’s coming up again as my husband and I plow through “Mad Men,” which I’ve seen compared to the Great American Novel and Cheever (we’re not allowed to talk about it right now because we just started season three). The point of this whole tangent is to raise the possibly ridiculous question about what makes something literary, and: is this important?

But your second question: No, I think the form does not lessen its seriousness. Do you? I’m thinking, in part, of graffiti art—like Banksy—is that making light of serious topics? I don’t think so.

Lara: Oh, I firmly believe the graphic medium does not lessen the importance. I think it’s just another way to tell a story. And, I think the form creates greater accessibility for people who might not read traditional narrative formats.

Jennifer: Do you want to tell us a little about the content of MAUS?

Lara: Sure. So, Art Spiegelman is an artist living in New York who decides he wants to tell his father’s story of surviving the Holocaust in Poland. In doing so, he hopes to also gain some clarity regarding their tumultuous relationship; they are not especially close. In Spiegelman’s rendering of the events, he draws the Germans as cats, and the Jews as mice—hence, MAUS. (There has been controversy surrounding Spiegelman’s depiction of Poles as pigs—here’s some information—though we aren’t getting into it here.) The story follows Art’s father through marriage and the Holocaust all the way to Rego Park in Queens, New York.

After reading the first volume, I really thought the author/artist was an asshole and not very sympathetic to his father. When I completed the set, I realized their relationship was much more complicated and couldn’t be boiled down to my initial perceptions.

Jennifer: That’s interesting. I felt absolutely no disdain whatsoever for the narrator. I was entirely sympathetic to him!

Vladek, Art’s father, survives Auschwitz, as does Art’s mother, Anja. The story, told graphically, is engaging—maybe at an especially deep level, because the reader is focusing on both words and images. Full attention is required, though for a shorter duration than a novel. But the story unfolds as a fairly prosperous Polish Jewish family loses every single thing—from money to dignity. Spiegelman takes away the humanity of everyone—Jews, Poles, Germans—and illustrates them as animals. Is this a mere artistic device? A little Walt Disney flair? Or is this a statement about the effects of Nazism? Under such a paradigm, we are all animals. All of us.

Lara: I totally agree that Spiegelman is saying that under such a paradigm, we are all animals, even the innocents. And you are right; Artie is not an asshole. However, I found him exasperatingly impatient and often rude to his father.

Jennifer: Lara obviously does not have a Jewish parent.

Lara: And then I figured out why the relationship was strained. It’s a bigger dynamic than might appear at first glance.

Jennifer: Exactly. Vladek and Anja survive Hitler, lose their first child, and end up in New York. But, in 1968, Anja commits suicide. Seriously, that struck me as so horribly tragic—to survive Hitler to kill oneself later. Ugh. Does this diminish her own story as a survivor?

Lara: I know! That was devastating on a number of levels. I don’t think it diminishes her story as a survivor. I think it’s a reality that some survivors faced. She lost everything including her first born, and ultimately couldn’t get past her own supreme sadness. That was heartbreaking.

Jennifer: So, Vladek embodies this survivor-spirit fully. He will survive. He will fight for life. In Poland, he had told his wife,

“No, Darling! To die, it’s easy . . . But you have to struggle for life! Until the last moment we must struggle together! I need you! And you’ll see that together we’ll survive!”

For Vladek, survival requires some nutty, if not misdirected, efforts. He hordes money, counts his meds obsessively, eyes everyone suspiciously—all in the name of survival. But, in truth, he really does survive. Was his wife a survivor too, even though she survived the Holocaust but not the rest of her life?

This just rubs his New York Jewish kid the wrong way. His son is coming from a different world. He marries a French woman, and suffers from depression in the contemporary way.

I think we’d be remiss to not talk about something that may be too awkward for you to talk about: national or ethnic identity—which, mishandled, can be racist and dangerous. Is there such thing as a Jewish identity? A Jewish character? Is Vladek’s instincts for survival indicative of his Jewishness? I’m not suggesting that Jews or any other ethnic group are genetically predisposed for some kind of deeply entrenched characteristic. Rather, is one’s cultural legacy ultimately and subtly woven into one’s being until survivalism or a kind of stubbornness is intrinsic to who he or she is? Vladek, through his life and the history of his people, will struggle to live. Don’t other groups have other experiences that shape identity, or form character? Is it safe to generalize about this?

In other words, how is the Jewish character revealed here—in Vladek, in Anja, in Artie? Vladek fights to live, Anja can’t take it any more, and Artie is another kind of man, part of another world.

Lara: That’s a really interesting question and something I am not sure you can assign to a specific religion or culture, but rather to humanity. I mean, think of the Lost Boys of the Sudan. They undoubtedly have after-effects from their life, being raised amidst violence, sometimes perpetrators of that violence, and then ultimately escaping (some of them anyway). They have their own survival story that could mimic parts of Vladek’s neuroses, but it has nothing to do with culture or religion.

Jennifer: Huh. I think there’s more to it. I’m really, personally, curious about it too. The instinct for survival might be universal, but the way that it looks may differ according to people. I’m not sure how to think about this—and I admit to dangers in generalizing. But, perhaps, if we’re too afraid to wade into the waters of how ethnicity shapes character, we’re missing something. Something really great!

As a writer, I seriously do obsess about this. Is there such thing as Jewish humor? I think so, Lara. One aspect of MAUS is that Spiegelman’s got the Jewish thing down. Think now about Woody Allen. He, too, might have the Jewish thing down. How did the Vladek who survived Hitler eventually become the Alvy Singer of Annie Hall? (And doesn’t Alvy have more in common with Artie? Artie is an artist, who seeks out his shrink and has a pretty goyish wife.)

Are you with me?

Think of other groups who have had their own unique experiences. Black Americans brought Spirituals out of Slavery. Then, this morphed into the Blues. How is it manifested today? And why is it manifested that way? Does the Black Experience result in a uniquely Black expression of Art?

Are you okay with this, Lara?

Lara: Of course I am okay with that. And of course I believe there are unique differences in race and culture that we can experience as observers (outside of that race or culture) or create (as a part of that race or culture). What I am trying to get at is that, with that, there is also a part of humanity—and our ability for resilience—that transcends race. I don’t think that we can say one race or culture is better at survival. I think all humans have a survival instinct—albeit stronger in some individuals than in others.

Jennifer: Okay, we’ll go with that. The role of race/ethnicity fascinates me. I admit it.

I just saw this amazing movie, by the way: The Railway Man. It’s about an English POW in Japan in World War Two. What blew me away is the extent to which humans can endure suffering. That may be universal. We can universally endure horrid things. The particulars of race and ethnicity may be revealed in the ways we endure, how it’s expressed. In the movie, the Englishman endures suffering like an Englishman. Vladek endures like a Jew. I read Twelve Years A Slave by Solomon Northup this year. How did he endure like a black man? Are these bad questions to ask? I do think they can be bad. First, we endure like humans; that must be the foundation of our discussion. Second, we endure in particular ways, unique to who we are.

Okay, I’ll wrap it up. I also found other themes fascinating in this book:

- More could be made about the use of animals to represent humans.

- The way God or the absence of God is worth noting. How did thinking about God change as a result of Nazism? Had it shifted already, or was this a point in which thinking about God drastically changed for the Jewish people? There are parts in here or a scene in here when Vladek says something about how people looked for God in the camps, but God was not here.

- This has been mentioned in other places. The question is raised in MAUS. Is it significant or even true or utterly misguided to ask why the Jews didn’t do more to resist Hitler? (Another film to consider: Hannah Arendt.) Did a lack of resistance allow for such evil? (Many, many people find the suggestion misguided.)

I’ll end with this question and my answer. Should these graphic novels be considered in the annual brouhaha surrounding the “Best Books of the Year”? Should MAUS be up against a Goldfinch or a Good Lord Bird for major book awards? (MAUS won a special, kinda ambiguous, 1992 Pulitzer Prize.)

I think not.

The Graphic Novel/Memoir is worthy of attention, full of artistic merit, and something you should give to your kids. But it’s not really literature. Don’t hurt me. Look for me at a future Comic-Con, dressed like Rapunzel. Wrong event?

Lara: Those are fightin’ words, Jennifer! Here’s what I will say. I think they should be included in the Best Books lists and could potentially go up against traditional novels. But they won’t ever win against them. Just like a comedic movie will never win best film at the Oscars. Which is why the Hollywood Foreign Press gets it right and has categories for best Drama and Best Comedy so that different film types can receive distinction. And, really, MAUS did receive worthy distinction. So maybe it’s nothing to worry about or maybe it’s something to consider. Who am I to say?

The good news is that we will be reading and reviewing this genre again next year. So you can expect more from us on this topic.

Jennifer: Wait. Stop. I’m pro the comedic movie winning an Oscar. So that’s not gonna work. The thing is this: This is mostly a visual art form. The artwork could probably stand alone, apart from the words. I don’t think the words could. Thankfully, we are not asked to separate the two. The Graphic Novel melds the two—words and image. But those words might not make it without the image.

Lara: Now we want to hear from you… do you read graphic novels? What are your favorites? Would you consider reading one now?

Up Next!

The year is coming to a close, which means we will share the best of what we read and fill you in our attempts at completing our 2014 Book Bingo card.

_______________________________________________________________________

Can’t get enough of Snotty Literati? Follow us on Facebook!

Want to read more from Jennifer? Check her out at www.jenniferspiegel.com

Want to see what Lara is up to? Go to www.onelitchick.com