Sympathy for the Devil?

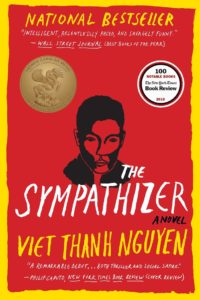

This month, Snotty Literati is going all Pulitzer on you. We read Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, the 2016 prize-winning novel—which is almost as complex as the Vietnam War. Can you even believe that this is his debut novel? The wildly complicated protagonist is of Vietnamese and French ancestry, a “bastard” or a “love child” (depending on perspective) working directly under a South Vietnamese General but secretly a Communist Agent—a spy. When Saigon falls and America fails, he—along with many others, including the General for whom he works—becomes a Vietnamese refugee in California. He’s a mole, then, in the U.S. Eventually, he returns to his homeland. But all of this speaks of the political landscape. At heart, this is a personal story of friendship, integrity, and passion.

Jennifer: So, it’s a big novel. Your thoughts first?

Lara: I see what you did there. Okay, I will say what we are both thinking. This is an important novel, told in a compelling voice that I really appreciated… but I am not sure I really liked it. And I can’t totally pinpoint why. And I promise that I put aside my usual dislike of Pulitzer’s choices (cough… The Shipping News and A Confederacy of Dunces …cough). In fact, he’s a really good writer! So, what do you think gives?

Jennifer: Um, you know, I don’t know! I’d agree, probably, with a little more hesitancy. I thought it was beautifully written, and even engaging. It felt a bit like an intellectual exercise. Is that such a horrible thing? Am I really suggesting that the book is too smart to be fun? I hope not. Again, I just don’t know. But I enjoyed it. Not as much as I wanted to. I think I felt like it could’ve been shorter?

Side note: I read two other books recently that had me “standing at attention” in an intellectual way the whole time: Barbara Kingsolver’s The Lacuna and Colson Whitehead’s Zone One. Kingsolver’s was about Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, while the latter was about the zombie apocalypse! (I know it sounds crazy to suggest that a zombie book could be intellectually stimulating, but it was!) Both required heavy-duty brain activity. I’ll be honest (and one of my best friends gave me Kingsolver): I loved Whitehead, but Kingsolver felt like a bit of a slog. This book, The Sympathizer, is somewhere in between. It is not a book in which one gets to read passively, and that’s fine. I can’t say that I always looked forward to picking it up.

Lara: It was beautifully written, though! And I liked the premise of this double agent who had the ability to really see both sides of any situation, employ empathy, and ultimately carry out his spy duties which often involved murder.

Jennifer: Actually, you just eluded to something—his ability to sympathize. The nameless protagonist says the following:

“My weakness for sympathizing with others has much to do with my status as a bastard, which is not to say that being a bastard naturally predisposes one to sympathy. Many bastards behave like bastards, and I credit my gentle mother with teaching me the idea that blurring the lines between us and them can be a worthy behavior.”

He has the ability to sympathize, then, and this begins to affect him profoundly, maybe blurring lines that were once black and white: legitimate and illegitimate child, friend and enemy, revolutionary and non-revolutionary.

Maybe special note should be made of his bastardliness (!). I think this novel artfully and subtly questions where one belongs, to whom one belongs . . . The idea of the refugee or the image of the boat people, which especially haunts the novel’s end, is connected to homelessness, being orphaned, another kind of existence as bastard. As a secret Communist, he is a political bastard. It’s all very complex! Were there surprises for you?

Lara: It’s super complex and—true Hollywood confession—the complexity could be the reason for my hella appreciation for the book but less love for it.

So from a surprise perspective? Lots of surprises. The book is told from this mole’s perspective, as he sits captured for his crimes in Vietnam where he has returned after exile in the U.S., writing his confession for review and approval by first the Commandant, and then the Commissar. It’s this confession that will determine his fate, his freedom. We know very little about him. He is nameless, as you mentioned. He’s a bastard, born out of wedlock to his mother and a French priest. His origin story or status as a bastard played heavily throughout the story, which surprised me.

Jennifer: I’d also say that the humor is surprising. This is a funny book. Very funny. (I heard the author do a reading for his follow-up short story collection, The Refugees, and he’s witty and charming—which comes through in his writing.)

Lara:. I appreciated the humorous insights our narrator shared, like this one:

“She cursed me at such length and with such inventiveness I had to check both my watch and my dictionary.”

The humor helps balance against the instances of torture. His complexity of character also surprised me.

“Not for the first time, I longed to tell someone that I was one of them, a sympathizer with the Left, a revolutionary fighting for peace, equality, democracy, freedom, and independence, all the noble things my people had died for and I had hid for.”

And, I loved the narrator’s observations. While the book was published last year, it takes place in the 1970s. His observations are brutally honest and entirely relevant today.

“Americans on the average do not trust intellectuals, but they are cowed by power and stunned by celebrity.”

And this:

“Don’t you see that Americans need the anti-American? While it is better to be loved than hated, it is also better to be hated than ignored.”

And more:

“Americans are a confused people because they can’t admit this contradiction. They believe in a universe of divine justice where the human race is guilty of sin, but they also believe in a secular justice where human beings are presumed innocent.”

Jennifer: I think the observations about America were great. Also, before moving on, I think the author plays around with the meanings of two words especially: sympathize and bastard. With whom does he sympathize, and what is a bastard?

Well, a few comments on the writing. I haven’t looked it up: to what is this book being compared?

I think I’ll compare it to two books. First, Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son (2013 Pulitzer-winner). This novel also “unpacks,” so to speak, some—not all—of the mysteries of a world we know little about. Despite the U.S.’s history with Vietnam, the region is still mysterious (Johnson plays around, in turn, with North Korea). Both books share this look behind a shroud of sorts. I hate to say it, but I might’ve “liked” Johnson’s novel a little better. That sounds trite. But anyway. This region is, maybe shamefully, an unknown. (So, here’s a rather superficial historical note that might be helpful.) Second, the end reminded me—maybe deliberately?—of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Oh, of course it was deliberate! Should I do my research? The spy is imprisoned, reminiscent of Raskilnikov’s final imprisonment. Both go through philosophical conversions. But, yes, this is a Dostoyevsky-level novel.

Lara: Well, you’ve lost me. I haven’t read Dostoyevsky. So I need to you dial it back a notch. Ha! I want to get back to your original question about if there were surprises. I think learning about the effort he has to go through to finalize his confession—perfect it, really—or actually, document it in a way that will be pleasing to the government higher-ups was morbidly fascinating. But what really knocked my socks off was seeing his interactions with the Commissar. That was great storytelling. And worth us not telling you too much so that you can discover it for yourselves, dear readers. Brilliant stuff.

Jennifer: Yes, it’s brilliant, albeit maybe Nihilistic? I wonder if the author would agree. Earlier, Bon, the narrator’s dear friend who is also a refugee (but not a Communist), discusses his existential situation:

“ . . .[M]y life once had meaning. It had purpose. Now it has none. I was a son and a husband and a father and a soldier, and now I’m none of that. I’m not a man, and when a man isn’t a man he’s nobody. And the only way not to be nobody is to do something. So I can either kill myself or kill someone else. Get it?”

This comes fairly early in the novel, but it might be the ultimate theme realized in the story. Ultimately, we are nothing? It is all for naught?

Lara: Not sure I am following you on this. Are you saying the theme is either kill or be killed? Well, when you are living in a war-focused environment, I would say that it would be hard to have a purpose beyond that. But you would have to be able to see yourself past the war or conflict. I don’t think Bon could. So for him, this life was essentially over.

Jennifer: I think the book makes an existentialist statement. And we’re all fools: Americans with their Hollywood-shaped wars, Vietnamese with their political ideologies.

But I also loved the author’s language, and that would be the thing I most want to impress upon our readers. Listen to this description of sex, which I can’t believe I’m quoting:

“Perhaps I would glimpse infinity when I lit her up with the spasmodic spark that came from striking my soul against hers.”

I say, Give him the Pulitzer for that!

Lara: I. LOVED. THAT. I would also give him the Pulitzer for this one, because, duh.

“I could live without television, but not without books.”

Jennifer: I guess I could live without TV.

Finally, this is a story about the immigrant experience, and the novel offers so many brilliant bits on the immigrant experience. I’ll just end with one passage:

“The General was deeply familiar with the nature, nuances, and internal differences of white people, as was every nonwhite person who had lived here a good number of years. We ate their food, we watched their movies, we observed their lives and psyche via television and in everyday contact, we learned their language . . . We were the greatest anthropologists ever of the American people . . .”

I love this, and it might be suggested that it makes this spy another kind of spy as well. We are all under surveillance, and there’s something naïve about our Americanness.

So that’s it. I think this is an intellectual book. If one has the patience and thirst for the complexity, it’ll be a great read.

Lara: I think you summed it up beautifully.

Next Up!

After all that scholarly stuff we, ironically, are diving into Elif Batuman’s The Idiot.

See you in October, Snotties!

_______________________________________________________________________

Can’t get enough of Snotty Literati? Follow us on Facebook!

Want to read more from Jennifer? Check her out at www.jenniferspiegel.com

Want to see what Lara is up to? Stay right here at www.onelitchick.com