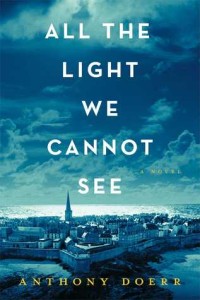

All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

Snotty Literati took on this mammoth 531-page National Book Award finalist by Anthony Doerr, since everyone was talking about it and it sounded really good. Because the title is in that delectable and possibly trendy first-person perspective, we’ll continue in that for now. We’ve got this sweeping backdrop of France and Germany during World War II. We meet Marie-Laure, a blind girl, who lives with her dad in Paris. They end up in Saint-Malo during the Occupation, possibly in possession of an amazing diamond from the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Parallel to this story, we encounter Werner, a German orphan. Werner ends up in Hitler’s Youth and in the War, because he’s an expert in radio technology. The War and the Occupation are on. It’s the kind of book that people are going to call stunning, because the prose is truly remarkable. BIG, HUGE, MASSIVE CAVEAT: WE WILL DISCUSS THE END. MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD!

Snotty Literati took on this mammoth 531-page National Book Award finalist by Anthony Doerr, since everyone was talking about it and it sounded really good. Because the title is in that delectable and possibly trendy first-person perspective, we’ll continue in that for now. We’ve got this sweeping backdrop of France and Germany during World War II. We meet Marie-Laure, a blind girl, who lives with her dad in Paris. They end up in Saint-Malo during the Occupation, possibly in possession of an amazing diamond from the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Parallel to this story, we encounter Werner, a German orphan. Werner ends up in Hitler’s Youth and in the War, because he’s an expert in radio technology. The War and the Occupation are on. It’s the kind of book that people are going to call stunning, because the prose is truly remarkable. BIG, HUGE, MASSIVE CAVEAT: WE WILL DISCUSS THE END. MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD!

Lara: I fell in love with the writing in this book! It’s exquisite. If I were someone who underlined favorite passages, my copy would be a highlighted mess. Fortunately, I read this on my Kindle. But, I also own it in hardcover. It’s that good.

Jennifer: I did read it on a Kindle, and my copy is a highlighted mess. It’s hard not to speak in clichés when talking about the writing. The prose is so fabulous that it’s worthy of that epic length. Though it’s almost impossible to pick out only a couple examples, I’ll try to do so.

There is vivid imagery:

“He sees a forest of dying sunflowers. He sees a flock of blackbirds explode out of a tree.”

There are many references to light:

“His handgun is black; it seems to draw all the light in the room toward it.”

There is figurative language:

“Seconds later, she’s eating wedges of wet sunlight.”

Really, I’ve got a highlighted mess. The prose is downright voluptuous. Actually, let me just say this. I’m not totally sure I’m right here, but I think I am. The book is almost entirely scene, as opposed to exposition; it’s all showing rather than telling.

In order for Doerr to accomplish this kind of book, there are time indicators—dates given—marking scenes. We jump around in time and location. We learn about the War through the happenings of the characters. There is no explanation or contextual information apart from a scene. So, Lara, my question for you is whether or not the story warrants the length? We agree on this prose. Maybe this is a moot point. What do you think about the story?

Lara: The story is one of the best I have read. I struggled a little with the timeline, but, ultimately, I loved the relationships in this book. Blind Marie-Laure and her lovely father, a locksmith who carved replicas of the city for his daughter to memorize and learn her way around; Werner and his sister Jutta, separated by the War and the oft redacted letters they attempted to share; Marie-Laure and her Great Uncle Etienne who grows out of his agoraphobia to protect her; Sweet Frederick, a curious bird-loving cadet and best friend to Werner; Volkheimer, the giant seemingly unfeeling comrade to Werner who’s full of quiet heart; Marie-Laure and Werner, the soldier who saves her.

It’s truly a heartbreaking work of staggering genius. Can I say that without getting sued by McSweeny’s or Dave Eggers? It is, though.

Jennifer: It’s okay to steal that from Eggers, though you mustn’t use the word redacted. WTF?

Lara: And you call yourself a writer? An academic? A scholar? To redact something is to censor or remove it for legal or security purposes. So remember all those blacked out sentences in the letters between Werner and Jutta? Redacted by the Nazis. As a superfan of The Office, I am surprised you don’t know the term. There was a whole episode about redacted emails.

Jennifer: Anyway. Here’s what I’m thinking. And, here’s where I spill the big news, so stop reading if you don’t want to know the big deal.

I loved it, but maybe not as much as you did. The ending wasn’t quite what I wanted. I’m okay with Werner’s sudden death, the lack of a big explosive love affair—even though I really wanted that. But I wanted more for Marie-Laure, more joy, more love. Etienne is the one who gets the happy ending here. He leaves his anxieties behind, and lives a full life. The others do not. Of course, maybe that’s the reality of war.

Lara: It is the reality of war and what Doerr captures so well.

“Werner can hear the Austrians two floors up scrambling, reloading, and the receding screams of both shells as they hurtle above the ocean, already two or three miles away. One of the soldiers, he realizes is singing. Or maybe it is more than one. Maybe they are all singing. Eight Luftwaffe men, none of whom will survive the hour, singing a love song to their queen.”

and

“An avalanche descends onto the city. A hurricane. Teacups drift off shelves. Paintings slip off nails. In another quarter second, the sirens are inaudible. Everything is inaudible. The roar becomes loud enough to separate membranes in the middle ear.”

and

“Sometimes at night, Werner sees Frederick when he is not there … Frederick; who did not die but did not recover. Broken jaw, cracked skull, brain trauma. No one was punished, no one questioned.”

And the scene where we lose Werner. It’s stunning and shocking. And while it takes away your hope of anything between him and Marie-Laure, it’s painstakingly realistic.

Jennifer: I hear you. This book definitely had some amazing aspects to it. It’s very picturesque. The miniaturization of a city, the lure of a diamond, the seduction of literature. That sharp visual imagery contrasting with the blindness of Marie-Lure who memorizes and counts steps, the precision of detail throughout the novel mirroring the intricacy of wires in a radio, the lasting effect of story from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea to the legend surrounding a mysterious jewel: this book is a work of Art.

That said, and I say this softly without too much confidence, I didn’t get immediately sucked into the story. I’m not sure I was ever completely engaged. I read it like I might walk through an amazing art museum, overwhelmed by the beauty but with a “hands-off” kind of distance. That’s it, distance. I felt a little removed from the novel, though I enjoyed it the whole time.

I’m not entirely sure why I felt this way. Was it because of the daunting length? (I don’t think so; I was sucked into The Goldfinch easily.) Was it because of the jumps in time? (I hope not, because I do that in my own writing.) Was it the ending? Did I feel let down? Disappointed? (I think not, since it only happens at the end!) For some reason, I was not intimately involved in this book, which was brilliant nonetheless.

The diamond thing may’ve bugged me.

Lara: The diamond was one of my favorite narrative threads!

Let me explain this diamond: There is a highly coveted blue diamond with a spark of orange in its center, known as The Sea of Flames. Prior to the War, the stone was housed in the Paris Museum of Natural History. Legend has it that the one in possession of the stone lives forever; however, everyone with whom he or she is close will suffer or die.

Marie-Laure’s father, Daniel LeBlanc, works as the principal locksmith at the museum. When Paris is evacuated, the museum director has three replicas and the original stone. He distributes three of the stones and keeps one, with Daniel LeBlanc being one of the carriers. The catch is that no man knows if his stone is the original.

“The locksmith tells himself that the diamond he carries is not real. There is no way the director would knowingly give a tradesman a one-hundred-and-thirty-three-carat diamond and let him walk out of Paris with it. And yet, as he stares at it, he cannot keep his thoughts from the question: Could it be?”

Sergeant Major Reinhold von Rumple, meanwhile, is on a mission to find the original Sea of Flames. Cancer-ridden and desirous of climbing within Hitler’s ranks, von Rumple is certain the stone is the answer to his prayers. He weeds out the fakes and, of course, Daniel LeBlanc had the original. But Daniel has been arrested and in a concentration camp. This leaves the unknowing Marie-Laure to defend herself and the stone. I thought this was a very compelling part of the story.

Jennifer: Oh, my goodness, Lara. I’m sorry to say this. It pulled me out of the story, just a little.

Lara: But wait! The legend of the stone was validated. Of course Daniel/Papa carried the original stone, and left it with Marie-Laure when he was arrested. Papa ends up in a concentration camp–not living forever. His loved ones survive the war. Knowing of the potential curse, Marie-Laure puts the stone out to sea, thus breaking the curse for future generations. I loved it. Absolutely loved it.

Jennifer: Lara, no matter what kind of heresies I’m saying, please know I thought this book a triumph, a wonder.

So what do you think about the title?

Lara: I knew you were going to ask that. I don’t know what it means. I cheated and went to the author’s site for clarity.

“It’s a reference first and foremost to all the light we literally cannot see: that is, the wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum that are beyond the ability of human eyes to detect (radio waves, of course, being the most relevant). It’s also a metaphorical suggestion that there are countless invisible stories still buried within World War II — that stories of ordinary children, for example, are a kind of light we do not typically see. Ultimately, the title is intended as a suggestion that we spend too much time focused on only a small slice of the spectrum of possibility.”

I love this. He’s nailed it. Pretty good thing since it’s his book.

Jennifer: A little reminiscent of Ernest Hemingway’s “Iceberg Theory,” which points out that most of the iceberg is beneath the surface of the water—and we are only seeing a fragment of it; in the same way, much of a story is invisible or beneath the surface of things.

So, yes, this is a brilliant book. It’s well researched too.

And that’s that. Lara?

Lara: Yes, that is that. And read this book. Read this lovely, heartbreaking work of staggering genius, please.

Next Up!

We are sticking with war, reading the 2014 National Book Award for Fiction, Redeployment by Phil Klay. This book of short stories should get everyone geared up for May and National Short Story Month. Until then, happy reading, Snotties!

________________________________________________________________________________________

Can’t get enough of Snotty Literati? Follow us on Facebook!

Want to read more from Jennifer? Check her out at www.jenniferspiegel.com

Want to see what Lara is up to? Go to www.onelitchick.com

One of the best books ever. Love the short chapters –helps move the book along, easier to read. Beautifully written, just enough romance, very interesting characters, mystery–just about everything a good book needs. Your discussion on the meaning of the title is interesting. Did the Germans see the light in the late thirties?Did Werner see the light?Did Werner’s sister see the light???

[…] Best Book Regardless of Publication Date: All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr. Thank goodness I read this book before it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction or I might never have picked it up. Those Pulitzer people aren’t the arbiters of such great taste. However, if I won one for say, book-blogging, I would brag the hell out of that shit… oh let me tell you. Here’s where my writing partner and I, aka Snotty Literati, reviewed All the Light We Cannot See. […]