Documenting The Undocumented

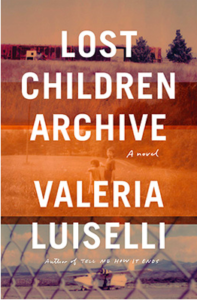

Valeria Luiselli is a Mexican author who lives with her family in New York. Critically acclaimed, pounding international pavement her whole life (her dad was a diplomat), a dancer, an activist, and a writer, she’s only thirty-five. Lost Children Archive is her first book written in English. (While many talk about her essay collection, Tell Me How It Ends, one also hears great talk about The Story of My Teeth, written and translated from Spanish.) Lost Children Archive is the story of a New York blended family (a mom and daughter with a dad and son) on a road trip across the States. The marriage is in trouble. The couple had been united in their work of documenting sounds: “surveying the most linguistically diverse metropolis on the planet.” Now, with diverging interests (undocumented children for her and Apaches for him), they embark on a life-altering journey.

Valeria Luiselli is a Mexican author who lives with her family in New York. Critically acclaimed, pounding international pavement her whole life (her dad was a diplomat), a dancer, an activist, and a writer, she’s only thirty-five. Lost Children Archive is her first book written in English. (While many talk about her essay collection, Tell Me How It Ends, one also hears great talk about The Story of My Teeth, written and translated from Spanish.) Lost Children Archive is the story of a New York blended family (a mom and daughter with a dad and son) on a road trip across the States. The marriage is in trouble. The couple had been united in their work of documenting sounds: “surveying the most linguistically diverse metropolis on the planet.” Now, with diverging interests (undocumented children for her and Apaches for him), they embark on a life-altering journey.

Lara: This is a fantastic and important book. It’s fantastically important. And written accessibly, despite containing topics people don’t always want to broach: The border, family separation, family dissolution, getting lost along the way. It was heartbreaking and beautiful. I loved it. This is the book not enough people are talking about. So we are, with our loud voices. Can anyone hear us?

Jennifer: I actually am at a loss for words, Lara. I loved this book. I don’t know quite how to discuss it. Before we get into specifics, I’ll say that I’ve really been thinking a lot lately about book ownership. As I’ve explained in a million different places (here’s the best one), my compulsion to buy books was challenged when my dad died, and we were forced to figure out what to do with his books. What was their value? And I’ve limited my purchases. I’ve gone out and bought a couple books after reading them. This is one of those that I want to own, to have.

I’m impressed with so much here. The book is a road trip novel, an experimental piece of fiction, a collage of narratives, of borrowed texts. Inside the Lost Children Archive, there are the Elegies for Lost Children. We move from Susan Sontag to Lord of the Flies, from audiobook to the plight of undocumented children, from Johnny Cash to Jack Kerouac. We are in Elvis-country and Apacheria. It’s a New York novel, and it’s magical realism. This is the book to read, folks.

You called it accessible, Lara. Is it? Were there mysteries for you?

Lara: Well, here’s the thing. When I picked it up and flipped through the initial pages, it felt like it would not be a book for me. I judged it not by the cover but the experimental-looking structure. Inventory lists start each chapter. Ugh. And because I was reading it for one of my book clubs, I also bought it on audio, thinking forced listening during my commute would ensure I finished it.

And then I didn’t want it to end.

So, I guess an initial mystery was the structure, which it turns out totally works.

It’s funny. I bristle at the term “magical realism.” I am too literal, and magical realism doesn’t work with how I read and process what I am reading. Am I fooling myself that this didn’t have elements of magical realism? I thought it was more exploring a child’s imagination. Am I getting hung up on semantics?

Jennifer: Yes.

Lara: NO WAY! I call BS on that. Moving on.

So, let’s get into the story a bit. We have a mother and her daughter, and a father and his son. These parents have embarked on a cross country road trip – to continue their professions as documentarians/documentarists (there is a difference that the book goes into). He wants to study the Apaches in Yuma, Arizona; she wants to tell the stories of undocumented children and their families. And in their tow are a ten-year-old boy and a five-year-old girl. Each chapter starts with an inventory of one of the family member’s boxes that they have packed and brought with them.

As they make their way south and across the southwest, the children get exposed to news and stories of lost children crossing the border, despite mom’s attempt to keep them shielded. These snippets take on a life-like form when during a stop somewhere in the southwest the two children wander off, imaginations gone wild and camera in hand, in search of the lost children.

Without giving too much away, Luiselli’s storytelling had me on the edge of my seat. I felt the anguish the mother felt discovering her children were gone. I felt the tension that the parents felt. And I experienced the wonder our young protagonists felt while on their innocent journey of curiosities.

How did the structure and storytelling work for you?

Jennifer: I’m so blown away by the structure and storytelling. I think it’s interesting that your initial urge is to layout the plot. My first urge is to gush over everything else—and I didn’t really want for you to say that the kids wander off. Because it took me by complete surprise. (There are other surprises.) I was so busy gushing.

I want to go back to that documentarian/documentarist thing. It’s a little weird. I think that one of the great accomplishments of this novel is that it leaves an impression. It’s impressionistic. This concept of documentation is scrutinized, pulled apart, flipped over, prodded. We talk about documenting the history of Apaches in Oklahoma. We talk about undocumented children. We talk about papers, documents. It’s very, very complicated.

This article by Denise Delgado says it well: “Each character in ‘Lost Children Archive’ documents and remembers in different ways: The mother-narrator is a documentarian producing a sound documentary on refugee children. The father is a documentarist creating a more esoteric ‘inventory of echoes’ recorded in places where Apache tribes and their leaders lived and died. Their two children play games in which they reenact stories of lost children and Apache warriors. Both mother and son record themselves reading and telling stories aloud. In this way the book contends with competing impulses around preservation, reportage and art — and what it means to bear witness. How to document a world in which young children ride ‘atop a train, their lips chapped, their cheeks cracked,’ to escape from one set of horrors to another?”

Long quote, but good. Hints at other themes: the ethics of reportage, art.

So here’s a hard question, Lara. What is this book about?

Lara: Oh, Jennifer. It’s about SO MANY things. I think, at the heart of it, it’s about storytelling and its importance. That we need stories to understand each other. That we must have ways of capturing stories of those who cannot do it themselves, yet who must be given voice. That requires documentation. Sounds, feelings, experiences, words, actions, everything. In this case, Luiselli is telling the story of a blended family unit, how they interact, love, laugh, and experience their lives. It also tells of this family’s connection to the larger world and an issue they have made part of their own world.

“Whenever the boy and girl talk about child refugees, I realize now, they call them ‘the lost children.’ I suppose the word ‘refugee’ is more difficult to remember. And even if the team ‘lost’ is not precise, in our intimate family lexicon, the refugees become known to us as ‘the lost children.’ And in a way, I guess, they are lost children. They are the children who have lost the right to a childhood.”

I am sure I am not fully articulating everything I want to say about this book. I can say this. I misjudged it. I am glad I got the audio version (and the book version). The audio version is one of the best produced I have ever listened to, embracing the importance of sound and sensory experience as you listen.

Jennifer: I do agree. I might add that I found it fascinating how Luiselli wove together miscellaneous snippets. For instance, David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” plays a major role here (there’s a pun in this, I think). Also, I found myself taking notes on things. In 2002, was there really an incident in which detainees in a detention center sewed their lips closed in protest? Yes. Did Lynne Cheney really write a lesbian romance? I never read it, but . . . So, what is this “Children’s Crusade” by Marcel Schwob? Thirty thousand medieval kids dead or sold into slavery? Oh, and THAT’S what this “Orphan Train” thing is all about . . . The Orphan Train Movement in the United States.

I learned a lot while reading this book. And Luiselli’s innovative, layered, hyper-smart book shows how reading can make you a better person, a person better acquainted with the human drama, a person who is more compassionate, a person who has a rich understanding of borders and crossing them and using story to document. Can you say, YOWZA?

Lara: You can say it! And you can cry and gasp and smile when you read or listen to it, because we did all of those things. Both of us. It’s that good. And it’s full of so many truths. I wrote this one down, which I think all parents feel more than once:

“I hope my children will someday forgive me, forgive us for the choices we make.”

Jennifer: Yes, we might end by saying that we really both had those gasping moments. These four family members hit us hard. When they’re at the Elvis Presley Boulevard Inn in Graceland, talking about how Apaches got their war names, these nameless family members (they are never identified by name—undoubtedly deliberate in a book about documentation) give themselves war names:

“And softly, slowly, we fall asleep, embracing these new names, the ceiling fan slicing the thick air in the room, thinning it. I fall asleep at the same time as the three of them, maybe for the first time in years and as I do, I cling to these four certainties: Swift Feather, Papa Cochise, Lucky Arrow, Memphis.”

When you read, you’ll know who’s who.

Lara, are there other books you’ve read that might be of interest to our readers?

Lara: Oh yes! Since our last write up, I have read Tell Me Three Things by Julie Buxbaum. I am a SUCKER for NON-dystopian/sci-fi/vampire Young Adult Lit. And if it has a sappy-sweet, meet-cute element with a happy ending? SIGN ME UP. It’s weird, I don’t love my regular/ contemporary/literary fiction all tied up in a pretty bow at the end (or with any saccharine at all), but I love it in my YA and this one delivered. I also loved the Dateline-exclusive tone of John Carreyrou’s Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup about Elizabeth Holmes and how she duped a lot of wealthy super important people to invest in her sham of a company, Theranos. Finally, Sally Rooney’s Normal People is just good. Very, very, very, good. And the cover is nice to look at.

Jennifer: I’ll only mention a few. I recently read Susan Orlean’s The Library Book, which really charmed me because the subject matter might—not that it should—cause you to yawn (libraries), and yet I was intrigued throughout! I read the graphic novel called I See Darkness by Reinhard Kleist, which is about Johnny Cash. I think it’s a must-read for fans. And I’m currently reading a book that’s bound to be on my best-reads-of-2019 list. Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black came out last year, and I almost missed it. My guess is that this piece of historical literary fiction about a runaway slave who is just a boy (bildungsroman too!) will soon be some epic film too. It’s fabulous.

Next Up!

We are hitting the summer with a super popular book, Tara Jenkins Reid’s Daisy Jones & The Six. See you in July!

______________________________________________________

Can’t get enough of Snotty Literati? Follow us on Facebook!

Want to read more from Jennifer? Check her out at www.jenniferspiegel.com and her latest book: And So We Die, Having First Slept. You can get it on Amazon right here.

Want to see what Lara is up to? Go to www.onelitchick.com.