Stoner: Stone-cold?

Stoner: Stone-cold?

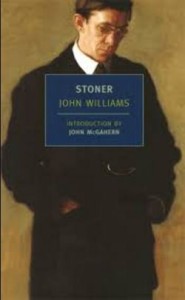

This month, Snotty Literati unintentionally continues its summer tour of human misery. Having traversed select literary offerings on suicide, brutality, abandonment, cancer, chemo, infidelity, and mental illness, we now wrap up August with existential angst! Stoner by John Williams is a quiet nouveau-classic novel (1965) about the lackluster and fairly miserable life of William Stoner, an unremarkable English professor at the University of Missouri.

Jennifer: So what did you think? It felt all old-fashioned, a little Downton Abbey-ish.

Lara: Is this where I admit that I haven’t watched a single episode of Downton Abbey?

Jennifer: Well, it’s no Mad Men or Breaking Bad, but Downton is like a really good cup of coffee. You just go, Ahhhhh. (But you don’t drink coffee either!) That’s what Stoner is like. Smooth, eloquent. How about this—Jane Eyre-ish?

Lara: Crap, I haven’t read Jane Eyre either. I’m a literary hack.

I will say that it’s a quiet book that deftly captures the emotional and physical scarcity of the time (pre- and post- WWI). Do you know of any happy books from that time period? Remember, it seems as though I really haven’t read very much – so, I could be opening a can of worms with that question. It seems to me, though, that the time was pretty bleak. Just over half way through the book, Williams writes:

“He was forty-two years old, and he could see nothing before him that he wished to enjoy and little behind him that he cared to remember.”

Isn’t that awful and beautiful? Williams can write misery.

He also writes of hope and possibility, although less frequently.

“As he sanded the old boards for his bookcases, and saw the surface roughness disappear, the great weathering flake away to the essential wood and finally to a rich purity of grain and texture—as he repaired his furniture and arranged it in the room, it was himself that he was slowly shaping, it was himself that he was putting into a kind of order, it was himself that he was making possible.”

That possibility is dashed with his heartless marriage and the drama of university politics—which I thoroughly enjoyed. I do love books centered around academia. But I digress . . . Interrupt me, Jennifer. Chime in.

Jennifer: Well, it is an academic or campus novel, which is a particular thing. I was wondering if you’d like it, because it doesn’t just center around academia. It centers around an English Department! So, like, it was great to me! I wondered how you’d take it.

But, well, the twenties were the Roaring Twenties. So I don’t know. I think, really, truly, this book—very bleak—speaks less of the time period and more about the human condition. For what do we live? Why work? Why love? Why get tenure or spread knowledge or write books? For what reason do we engage in scholarly endeavors? The book is really in the family of the great existential novels: Albert Camus’ stuff, Waiting for Godot, etc. So it arrives, more or less, at the idea that it’s all meaningless.

Consider this beautifully written passage on the death of Stoner’s parents:

“He turned on the bare, treeless little plot that held others like his mother and father and looked across the flat land in the direction of the farm where he had been born, where his mother and father had spent their years. He thought of the cost exacted, year after year, by the soil; and it remained as it had been—a little more barren, perhaps, a little more frugal of increase. Nothing had changed. Their lives had been expended in cheerless labor, their wills broken, their intelligences numbed. Now they were in the earth to which they had given their lives; and slowly, year by year, the earth would take them. Slowly the damp and rot would infest the pine boxes which held their bodies, and slowly it would touch their flesh, and finally it would consume the last vestiges of their substances. And they would become a meaningless part of that stubborn earth to which they had long ago given themselves.”

Happy, isn’t it? The question for Williams is whether he thinks this is life for everyone. I think he would say that it is.

Lara: I don’t know that one story can serve as the author’s statement on life. Or maybe it’s his statement on life at that time. . .which I think was dismal for a lot of people. It was also a time that people were starting to move away from living off of the land and pursuing other jobs. Stoner presumes he will follow in the footsteps of this father, and be a farmer. But it’s his father who actually encourages Stoner start at the University.

“ ‘I never had no schooling to speak of,” he said, looking at his hands. “I started working on a farm when I finished sixth grade. Never held with schooling when I was a young’un. But now, I don’t know. Seems like the land gets drier and harder to work every year; it ain’t rich like it was when I was a boy. County agent says they got new ideas, ways of doing things they teach you at the University. Maybe he’s right. Sometimes when I’m working in the field I get to thinking.” He paused. His fingers tightened upon themselves, and his clasped hands dropped to the table. “I get to thinking—” He scowled at his hands and shook his head. “ You go on to the University come fall. Your ma and me will manage.” ”

But Stoner doesn’t stay with studying Agriculture. It was a required course in English literature that changed the trajectory of his life. I do love that.

Jennifer: I do too. He embraces the scholarly life. Maybe you can explain this better than I. Why does he do this?

Lara: That’s a good question. He struggled in that first course—failing that first exam. He clams up when his professor calls on him to explain one of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Despite this, the professor takes an interest in him and I think it’s that nudge, that sense that he can do something and be a part of something that causes Stoner to change his course.

Jennifer: Well, he’s enamored, in love. Smitten with the Quest. Also, he’s a refugee of sorts—fleeing the farm—and a dissident—studying literature! This is fairly unexplored in the novel, though it’s pretty interesting. Williams writes about the role of the university, and I loved a lot of it:

“It’s for us that the University exists, for the dispossessed of the world; not for the students, not for the selfless pursuit of knowledge, not for any of the reasons that you hear.”

These are the words of Dave Masters, who dies in WWI, and becomes sort of monolithic or heroic or symbolic in Stoner’s life, a kind of totem? Yes, a totem. Later, Stoner recalls how Masters said,

“. . .something about the University being an asylum, a refuge from the world, for the dispossessed, the crippled.”

Herein resides Stoner. And, frankly, I get this. I know that apart from my mom-garb and my writer-life, I’m an academic, wholly, happily. I love academia! I also dislike university politics too, but, hey, the myopia of scholarly endeavor is fab. And it’s a hideout for us misfits! There, we discuss Big Ideas and we think others are discussing them, too. We Read Books! There’s an artificiality about it; it’s a haven. I think Williams gets at this.

But it’s an empty life if done solely in that myopic fashion.

“As Archer Sloane [an old professor/mentor] had done, he realized the futility and waste of committing one’s self wholly to the irrational and dark forces that impelled the world toward its unknown end; as Archer Sloane had not done, Stoner withdrew a little distance to pity and love, so that he was not caught in the rushing that he observed. And as in other moments of crisis and despair, he looked again to the cautious faith that was embodied in the institution of the University. He told himself that it was not much; but he knew that it was all he had.”

Don’t you want to say, Shit, Man? Depressing!

We should mention that he has a love affair, in middle age, with another academic. A grad student. While happy, it ends tragically. I think its overall miserableness contributes to the big, existentialist theme. I am interested in one comment someone—and forgive me for not knowing who it was—made on social media. This person mentioned that the novel did haunt her and she spent a lot of time thinking about whether or not Stoner could’ve done anything differently. Could he have, in the world of this novel, lived another life? It’s a good question.

Lara: I am not sure he could have done anything differently. If he did, it wouldn’t have felt true to the rest of the novel. I did love their affair, though. His wife Edith was awful and manipulative. I am not defending it, mind you. I just loved how he wrote about his time with Katherine.

“In his forty-third year William Stoner learned what others, much younger, had learned before him: that the person one loves at first is not the person one loves at last, and that love is not an end but a process through which one person attempts to know another.”

And then this:

“They made love, and talked, and made love again, like children who did not think of tiring at their play. The spring days lengthened, and they looked forward to the summer.”

And, finally, this:

“In his extreme youth Stoner had thought of love as an absolute state of being to which, if one were lucky, one might find access; in his maturity he had decided it was the heaven of a false religion toward which one ought to gaze with an amused disbelief, a gentle familiar contempt, and an embarrassed nostalgia. Now in his middle age he begun to know that it was neither a state of grace nor an illusion; he saw it as a human act of becoming, a condition that was invented and modified moment by moment and day by day, by the will and the intelligence and the heart.”

Sigh. . . lovely. Just lovely.

Jennifer: So then he dies. Williams writes,

“It occurred to him that he ought to call Edith; and then he knew that he would not call her. The dying are selfish, he thought; they want their moments to themselves, like children.”

My last question. You’re normal, not in need of an academic calendar (I’m forty-six, and I still think in terms of semesters) or a college hideout. Why is this novel worth your attention?

Lara: I think it’s worthy of attention because Williams writes so well of the human condition. The longing, the desperation, the few fleeting moments that brought Stoner joy. Despite the bleakness, it’s beautifully written. We need to keep beautiful writing, not just genre-plot-driven-series in the forefront. We need to keep reading literature and not just books.

Jennifer: I fully agree. This is a book that explores humanity; it does so beautifully. Though its conclusion is bleak, Williams was terribly gifted. I did love it.

Next Up!

We are so excited to be discussing Yaa Gayasi’s debut Homegoing.

See you next month!

_______________________________________________________________________

Can’t get enough of Snotty Literati? Follow us on Facebook!

Want to read more from Jennifer? Check her out at www.jenniferspiegel.com

Want to see what Lara is up to? Go to www.onelitchick.com