The Good Lord Bird: Meeting Heroes in Fiction

The Good Lord Bird: Meeting Heroes in Fiction

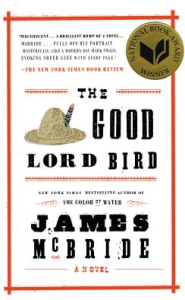

This is our first explosive Snotty Literati of the New Year. We decided to begin with the National Book Award-winning novel by James McBride, The Good Lord Bird. McBride, also the author of the beloved memoir The Color of Water (and two other novels), has spun a wild tale about the famous abolitionist John Brown and his attempts to end slavery in pre-Civil War America. In McBride’s novel, Brown ends up accompanied by a slave boy named Henry Shackleford—who is masquerading as a girl. Henry is Henrietta! Even Brown doesn’t know! When Brown leads his tragic raid on Harper’s Ferry, the book reaches its powerful climax.

Lara: I think it was this time last year that The New York Times burst out of the gate proclaiming that George Saunders’ Tenth of December would be the best book of 2013. Well, I am here to say that The Good Lord Bird by James McBride was the best book of 2013, which is why it won the National Book Award for Fiction for 2013 (take that, George) and I think it will be in my top three for this year (of my own reading), if not the favorite.

Jennifer: Yikes, Lara. We mentioned “explosive” above. I guess you’re not hesitating. I’ll go for it too. I’m a little obsessed, personally, with the concept of the “Great American Novel.” I’m still waiting for someone to ask me to teach this class. I’d do Gatsby. I’d do Huck. The last book I added to my imaginary syllabus was Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. I find the idea of capturing the essence of America, or “writing America,” fascinating. I’d now add James McBride’s book to the required reading. He captures something uniquely American, and it’s Americans of all colors of which I’m speaking. Blacks and whites together in America.

Lara: The Good Lord Bird should absolutely be required reading. It covers such a horrendous period of American history that can’t ever be repeated. What I find impressive is how much humor McBride is able to put into a story about slavery. The story covers maverick abolitionist John Brown (a true character in our history) and pairs him with a boy named Henry, who Brown mistakes for a girl. Henry doesn’t have the time or courage to correct Brown as the boy’s father has just been shot. In the hubbub, Brown swoops up “Henrietta” and she becomes the face of freedom on Brown’s journey to Harper’s Ferry.

Jennifer: Okay, so it’s got three particular traits worth noting: humor (the situation is intrinsically funny), language (there are tons of examples, such as this one: “He looked rough enough to scratch a match off his face”), and content. Speaking specifically about the latter trait, this book might best be compared to Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Though both are narrated by boys and both deal with what happens when people are confronted with the realities of racism, I’m thinking more in terms of how these two books capture uniquely the American experience. This is how Americans experience race. This is how Americans come to terms with morality, with good and evil. This is how Americans fight their battles. John Brown is one kind of American, the fierce and independent and downright holy kind. He’s a wild man, and he evokes images of rugged individualism, of “Little House on the Prairie” (which I’m totally into). Henry/Henrietta/”The Onion” (his nickname) is another kind: innocent but bruised, childish but wise, free. This is a book about freedom, freedom American-style.

Can you believe this? I sound like I’m about to break out into the National Anthem

Lara: I will queue the band. It is about those things and there are some strong paradoxes. Brown is this moralistic crusader against slavery—even if some don’t want to be freed—yet he has no problem murdering people for it.

Jennifer: I suppose that might give some people pause. John Brown resorts to violence to end slavery. He takes up arms. He is a violent man. This goes against every pacifist bone in a Gen X do-gooder’s body. (Hey, we’re writing this up, by the way, on MLK day.) First, I’m fine with Brown’s tactics. There comes a point, I’m sorry to say, when it’s gotta happen. Second, McBride did an amazing job of making this insane killer loveable, good, and God-fearing. Brown is one of the best Christian characters in contemporary lit. I’m really blown away by how McBride turned a violent man into one very much devoted to doing good.

Lara: What got to me more was the horrible treatment of blacks. Look, I know it happened. It didn’t make it easy to read. It was hard to read blacks denigrate themselves, to read Onion’s first crush (Pie) talk about the slaves penned up outside the brothel, and to even read Onion talk about his friend Bob and other blacks with such hateful and hurtful language.

Jennifer: Let’s publicly note at this point that Lara doesn’t see Tarantino films.

Lara: Don’t write me off as some sheltered white girl. I saw Pulp Fiction, I just can’t see any of his other films.

Jennifer: Well, there’s a lot of talk about portraying American history and using the N-word. Django Unchained. Brilliant film. It’s been suggested that Tarantino almost revels in the use of the N-word, and he gets away with it because his cause is ultimately righteous. I don’t think this is true, but people say it. I think Tarantino is just telling it like it is. I’m a fan.

I digress? I do not. McBride is far gentler—most of the time—than Tarantino, but the ugly language shows up. If you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen? Hell, no! You must stay in the kitchen. America is in the kitchen. Leaving the kitchen is cowardly. I respect McBride tremendously for the brutality he shows—which is very much softened in this novel. Lara is terribly squeamish.

So, yeah, there’s a lot of ugliness here. McBride, though, renders it beautifully.

Lara: Before I sound like a total wuss, it’s all in the name of respect. I just really don’t like people being hateful towards another. For any reason.

Jennifer: I know, Lara, I know. The question is a tough one. Is this language ever appropriate? In what context? I know, as a teacher, one of my biggest freak-out sessions is when books are dismissed because the language is offensive. Is the language serving a purpose? Is it true to the characters’ reality?

Lara: And yet this story has to be told and it has to be told the way it happened, as painful as it is.

In The Good Lord Bird, McBride helps us remember where we all came from, and that this ugly time wasn’t so long ago. He does a great job showing us the flawed leaders of the abolitionist movement, Brown being a perfect example. And he does a number with Frederick Douglass as a married man living with his black wife and white mistress (totally true!) and then has him chasing after 12 year-old Onion (not true, but a potentially possible scenario considering how Douglass appeared to have actually lived).

You know, McBride was interviewed about this book and he had a great comment about Douglass’ flaws: “Listen, don’t meet your heroes. If you meet your heroes, you are always going to be disappointed.”

Jennifer: I think that’s a great and true quote. When we meet our earthly heroes, we’re meeting mere men and women. McBride may completely humanize a murderous Brown, but he makes Frederick Douglass a little sleazy. (Harriet Tubman shows up too; she looks good.)

This brings me to two things. First, I want us to be super clear about this. McBride takes some real life historical figures and builds his fiction around them. So, when we’re meeting these heroes, we’re doing so through a veil, if you will—the fabric of fiction.

Second, I’m dying to say this. I’ve come clean more than once about my own religious stance. One of those crazy Christian types! I’ve also written much about my own alienation, if you will, from other “Christian writers.” I’m just not into what they tend to be into. In fact, I’m always wondering if I’m going to be excommunicated for some of my stories in The Freak Chronicles or officially reprimanded for my worldliness in Love Slave. I use bad words. I freakin’ adored Pulp Fiction. I’m constantly getting into trouble, which is shockingly ironic. In the secular world, I’m a goody-goody. In the sacred, I’m practically the Whore of Babylon.

All this to say, I’m vigilantly on the lookout for Christians in the Arts who are doing it the way I want to do it. Marilynne Robinson writes like a boss (never said that before!). The woman is a Calvinist, folks. James McBride doesn’t mince words one little bit. He writes the truth. Seriously, he’s up there with the likes of Mark Twain! You can’t say that about too many people! And, well, he’s a Christian. Not a Christian writer. But a Christian who writes. I’d be remiss if I didn’t bring this up. McBride is not writing second-rate fiction. Sadly, that often seems to be the case. For this reason, I’ve chosen to completely disassociate myself from the Christian fiction genre. (They’d disassociate from me too, in all fairness.) But I’d like my genre to be McBride’s genre.

Lara: He’s a masterful storyteller, is what he is, regardless of any religion he practices. When you start a book with these words:

“I was born a colored man and don’t you forget it. But I lived as a colored woman for seventeen years.”

You are instantly pulled in. Passages like these keep you going:

“She wore a flowered blue dress of the type whores naturally favored, and that thing was so tight that when she moved, the daisies got all mixed up with the azaleas.”

“…dying as your true self is always better. God’ll take you however you come to Him. But it’s easier on a soul to come to Him clean. You’re forever free that way.”

I just loved it. As hard as it was at times, I loved it.

Jennifer: Some closing remarks, since they’re shutting us down here at Paradise Bakery.

I thought there was some genius in how McBride portrays the moral outrage of Brown. There’s really something pure and forceful—and blind—about it. At one point, McBride writes of Brown,

“The Old Man [Brown] was sure, he spoke with the strength of a man who knowed hisself.”

What a rare thing, you know? He knew himself. He was true to himself. This allowed for a certain holiness, I think. McBride is really gentle with this bloody but good man.

I also think McBride shares quite a bit of wisdom in this book. There’s an irony that’s very clever. While The Onion is deceiving everyone because he’s dressed like a girl, the book shows the depths of deception—the way slavery forces a lie upon a culture. McBride writes,

“Truth is, lying come natural to all Negroes during slave time, for no man or woman in bondage ever prospered stating their true thoughts to the boss. Much of colored life was an act . . .”

Elsewhere, another slave says to The Onion,

“Their [the slaves] job is to tell a story the white man likes. What’s your story?”

All of this then leads to this amazing finale at Harper’s Ferry, in which The Onion experiences his own moment-of-truth very reminiscent of Huck’s own awakening to injustice. Interestingly, Huck abandons religion, and The Onion embraces it. But it’s connected to being true to one’s story.

Finally, I’ll say there were some things I didn’t love. I hate to say it because I loved much more than I didn’t. BUT sometimes I got a little weary of chasing after who was who, and where they were all going.

Lara: And if you don’t take our words for it, take the fact that it won the NBA for Fiction in 2013. But you really should take our words for it. I mean, you are reading this column, right?

Next up: We dive into pop-fiction with Catching Fire by Suzanne Collins, and then we return to our literary territory with The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt.

_______________________________________________________________________

Can’t get enough of Snotty Literati? Follow us on Facebook!

Want to read more from Jennifer? Check her out at www.jenniferspiegel.com

Want to see what Lara is up to? Go to www.onelitchick.com

I loved reading this! You guys are so good. But didn’t you think John Brown knew the entire time about Henry/Henrietta? I didn’t think he did until the very last minute.

[…] 4. The Good Lord Bird by James McBride (2013). Earning The National Book Award for Fiction, The Good Lord Bird is a humorous and provocative historical novel chronicling Abolitionist John Brown and his storming of Harper’s Ferry. McBride creates a motley crew, while throwing in some well-known members of the anti-slave movement. A truly great read. […]