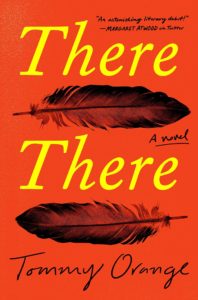

There There Is Over Here

Tommy Orange’s debut novel is the focus of our attention this month. Set mostly in Oakland, California, multiple characters with unique voices thread together a narrative about urban Native Americans attending a large-scale Powwow. The title alludes to both Radiohead’s song and to Oakland’s own Gertrude Stein who said, “ . . . there is no there there.” The impact of the novel is intense. There is a grand finale at the Powwow. And we’re still feeling the waves. . .

Tommy Orange’s debut novel is the focus of our attention this month. Set mostly in Oakland, California, multiple characters with unique voices thread together a narrative about urban Native Americans attending a large-scale Powwow. The title alludes to both Radiohead’s song and to Oakland’s own Gertrude Stein who said, “ . . . there is no there there.” The impact of the novel is intense. There is a grand finale at the Powwow. And we’re still feeling the waves. . .

Lara: Here’s what I am going to start with. There There is one of the first books I have read in a very long time where you could feel the tension build up across the pages and into a legitimate climax. A climax that had me audibly gasping and shaking my head in utter shock, disbelief, sadness, and anger. It kind of wrecked me. We need books that do that. The fact that this story feels so very real and possible makes it even more shocking. But let’s take a step back. Orange begins the book in an almost academic approach, accounting for horrible atrocities against Native people. What did you think of his approach in opening the novel this way?

Jennifer: Um, well it was academic. An essay. There’s also an academic “interlude” in the middle. I was fine with it. The book is really made up of multiple voices, so it seemed right to me. I will admit to not loving the book as much as you did. Don’t get me wrong. I really liked it. I just didn’t love it. I should note, however, that the writing is very good; it’s lovely prose.

Lara: It was so academic that it first read as non-fiction to me, and I switched from my signed hardcover (swoon) to an audiobook. I am justifying this switch by knowing the value of oral tradition in the Native American culture. The audio version is narrated by four Native people which brought a richness to my experience, and took away the sensation that it was a textbook history lesson (only at the beginning). One of the things Orange did really well was create a multi-layered story with fully drawn characters. Can you do a high-level overview of the storyline and then let’s talk about the characters?

Jennifer: Sure, but first let’s emphasize that the academic talk is short-lived, and this is mostly storytelling. I felt like the essay stuff was powerful, contrasting with flesh-and-blood stories. In the “Prologue,” Orange writes,

“Plenty of us are urban now. If not because we live in cities, then because we live on the internet. Inside the high-rise of multiple browser windows. They used to call us Sidewalk Indians. Called us citified, superficial, inauthentic, cultureless refugees, apples. An apple is red on the outside and white on the inside. But what we are is what our ancestors did. How they survived. We are the memories we don’t remember, which live in us, which we feel, which make us sing and dance and pray . . .”

They are the there there? Maybe? This academic-speak is the context of a human story. In fact, there’s something reminiscent of The Canterbury Tales here. So the story . . . Dene Oxendene plans to capture the urban Native experience on film by setting up a StoryCorps-like booth at this Powwow. The Powwow is a kind of There There too, a gathering of displaced people. Characters make the pilgrimage for various reasons—to affiliate, identify, claim, cherish, remember what is lost. Dene is there with a grant to film the stories, and we are introduced to seemingly disparate individuals who turn out to be linked in complex familial histories. The characters are memorable, as are their stories. Orvil, a kid, will dance at the Powwow. He learned how from YouTube videos. Jacquie Red Feather, Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield, and Blue – the women – are all interconnected too. It becomes a family saga, an epic about history and consequences.

I think I’d say the three most memorable aspects for me would be the rich portrayal of women, Orange’s play upon contemporary life, and the Alcatraz stuff. More soon. What is sticking with you?

Lara: Well, I loved how the layers peeled away and exposed how characters were connected or related. I especially loved Orvil, a teenager who wanted to remain connected to his culture and dance at the Powwow despite knowing his brothers would scoff. Women featured heavily with rich backstories and were beautifully flawed. Edwin, a thirty-year-old man still living at home, searching for a father he never knew and desperately trying to get outside of his room and into the real world, was endearing and awkward. I don’t know if we have enough time to cover how much I loved in this book. I will tell you that I want a follow up. I know there won’t be one; this isn’t the type of book that will result in a sequel, but, man, I would love one.

Jennifer: Well, I’ll develop some of these things I loved. First, I thought he did a great job with the women, which is super admirable. Second, I really loved the way Orange hit upon certain modernities—like there’s a drone in here and there’s 3D printing and social media. These could easily be misused in a narrative, as if the author is “trying” too hard to be culturally chic. But Orange somehow or other reveals the irony in the situation. These are people with the land literally pulled out from under them, always looking for “there there,” and are now in this Brave New World where drones fly overhead. Finally, I thought the allusion to the November 1969-June 1971 Occupation of Alcatraz was pretty fascinating. I think Orange did a great job in revealing how crazy complicated the Native American experience is.

What did you think about the voice or the language? Some lines were so poignant:

“Jacquie can’t remember a day going by when at some point she hadn’t wished she could burn her life down.”

Lara: I thought Orange did a fantastic job creating distinct voices for all twelve characters. What I think is probably most important is that by writing There There, he is creating a voice for other Natives. One character, telling his story, says:

“When you hear stories from people like you, you feel less alone. When you feel less alone, and like you have a community of people behind you, alongside you, I believe you can live a better life.”

That’s exactly what Orange is doing and we need more of it. Natives need more than the words of Louise Erdrich and Sherman Alexie (scandal-aside).

Jennifer: I agree, and I’m going to resist making any comparisons with Alexie (whose work I’m more familiar with than Erdrich’s and whose work I love)—because I do wonder if it’s a problem, and if it’s also contributed to Alexie’s downfall. It’s no easy task to be the spokesperson for an historic legacy, and it’s almost as if that’s what is expected of the Native writer. Maybe Orange’s real gift to us is in showing the multiplicity of voices.

His characters are complex and different, but they share a history. I’ll close with this passage:

“This is the thing: If you have the option to not think about or even consider history, whether you learned it right or not, or whether it even deserves consideration, that’s how you tell you’re on board the ship that serves hors d’oeuvres and fluffs your pillows, while others are out a sea, swimming or drowning, or clinging to little inflatable rafts that they have to take turns keeping inflated, people short of breath, who’ve never even heard of the words hors d’oeuvres or fluff.”

Lara: I think that’s when Orange dropped the mic, err, pen. And with that, we say farewell until October.

Next Up!

Join us in October when we discuss Jon McGregor’s Reservior 13, longlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2017, and what the Man Booker Prize is all about.

Until then… Happy Reading, Snotties!

______________________________________________________

Can’t get enough of Snotty Literati? Follow us on Facebook!

Want to read more from Jennifer? Check her out at www.jenniferspiegel.com

Want to see what Lara is up to? Go to www.onelitchick.com